Over the coming weeks we are going to be sharing all of the technical details behind our evals engine. This is the first instalment in that series, which discusses the motivation, architecture and high level benchmarking work we have done. Subsequent posts will dive into different aspects of this in much more detail, along with experiment findings, implementation details & code for reproducing.

The problem - Your experts define quality. But they can't review everything.

Teams building AI applications face an uncomfortable choice: manual expert review that's accurate but doesn't scale, or automated evaluation that scales but doesn't match your standards.

Numeric scores from LLM-as-judge are unstable, poorly calibrated, and often meaningless. Boolean assertions are reliable but lose granularity—you can check if a response was hallucinated, but not how badly. Neither approach scales to the nuanced quality judgments that production systems require.

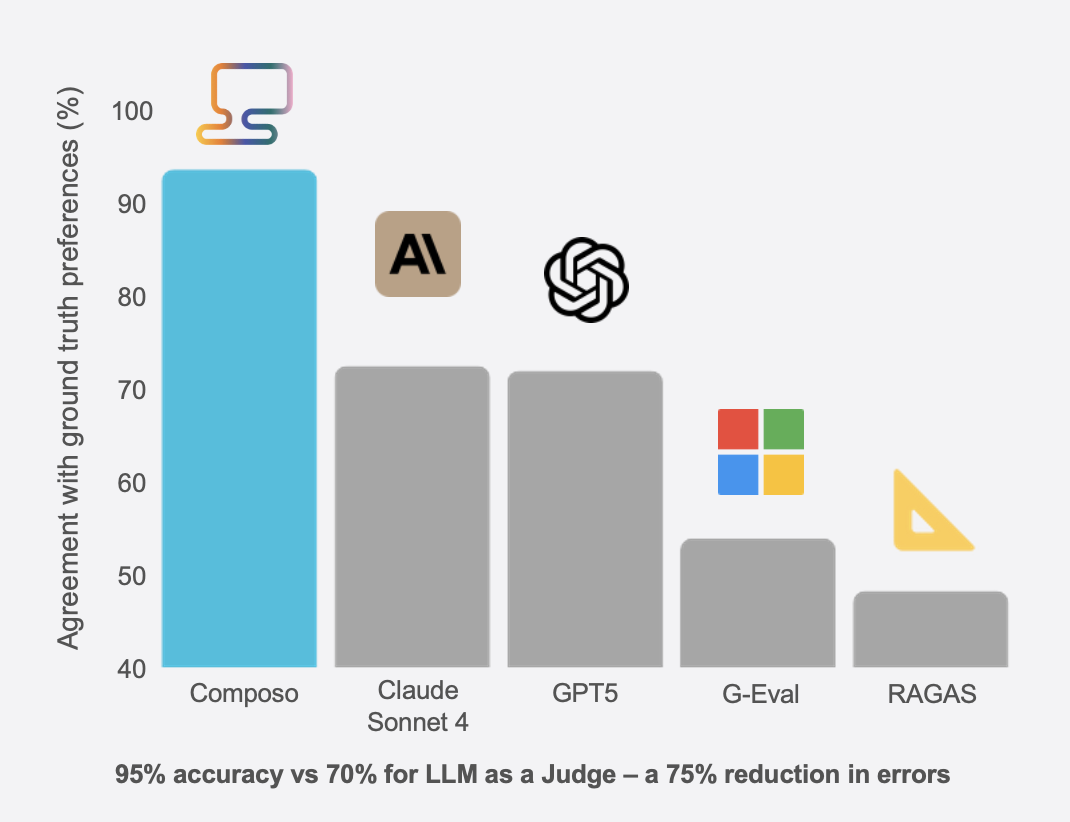

Composo provides an alternative: 95% agreement with expert evaluators, compared to ~70% for LLM-as-judge approaches.

The system uses a generative reward model architecture that produces deterministic, well-calibrated scores from single-sentence natural language criteria. It works out of the box without labelled data, learns from each customer's evaluation history automatically, and can optionally incorporate ground truth annotations and external data sources.

Evaluation isn't just a testing concern—it's the feedback loop that shapes your entire LLM application. When that feedback loop is noisy, the costs compound.

Bad prompts ship to production. If your evaluation can't distinguish between a 0.6 and a 0.8 response, you can't tell whether your prompt changes actually improved anything. Teams end up shipping changes based on noise, or worse, avoiding changes because they can't measure impact.

Regressions slip through. A model update or prompt tweak that degrades 15% of responses may not move your average score if that score was already bouncing around by ±20% due to evaluation variance. You discover the regression when users complain, not when you could have caught it in CI.

A/B tests mislead. When your evaluation metric has high variance, you need dramatically more samples to detect real differences. Teams either run underpowered tests and draw false conclusions, or give up on quantitative comparison entirely.

You can't automate quality gates. If you don't trust your scores, you can't use them to block deployments or trigger alerts. Every release requires manual review, which doesn't scale.

Expert time gets wasted on routine review. Your domain experts spend hours reviewing outputs that are obviously fine, instead of focusing on the edge cases and disagreements where their judgment actually matters.

The irony is that teams adopt LLM-as-judge specifically to automate evaluation—and then can't trust the automation enough to act on it.

LLMs face significant challenges when used for evaluation tasks. Recent research systematically testing LLM judges across multiple models and scoring formats has confirmed patterns we've observed in production: numeric scores are fragile, poorly calibrated, and often misleading.

LLM judges don't degrade gracefully as output quality worsens. Instead, scores saturate quickly and then stop distinguishing between moderate and severe problems. A response with 20% hallucinated content and one with 60% hallucination may receive identical scores because the judge's output has already hit a ceiling.

Controlled experiments demonstrate this clearly: when researchers introduced progressively more errors into text passages, scores plateaued early and collapsed into narrow bands. Light and heavy corruption became indistinguishable. The expected linear relationship between quality and score simply doesn't exist—instead, you get discontinuous jumps, long flat stretches, and clustering around arbitrary values.

The same response with an obvious hallucination can receive 60% on a 1-5 scale, 30% on a 1-10 scale, and 85% on a 1-100 scale. These scores reflect the model's sensitivity to scale configuration rather than any calibrated understanding of quality. Without explicit training on what different score values mean, the mapping from quality assessment to numerical output is essentially arbitrary.

Testing across multiple formats—1-10, 0-1, -1 to 1, and letter grades (A-E)—shows that none produce a smooth correlation with actual quality. Changing the numeric range shifts the appearance of curves but doesn't address the underlying instability.

Even with temperature set to zero, LLM scoring exhibits instability. While reasoning and judgments have become more consistent in recent models, final numerical scores still vary across runs. If you receive a score of 0.4, the true mean might actually be 0.6—you won't know without repeated sampling.

This means you're not getting a point estimate; you're sampling from a distribution. What looks like a single score is actually a spread, and neighbouring quality levels often overlap entirely.

Scores from different LLM judges cannot be compared. GPT and Claude may both produce medians that rise with corruption density, but they differ in scale and behaviour. The same passage scored lower by one judge may be scored higher by another. Any score is only meaningful relative to a specific, fixed judge configuration.

Getting reliable results from LLM-as-judge requires extensive prompt engineering: detailed rubrics, few-shot examples, careful scale definitions. This optimisation work is domain-specific and often needs to be repeated for each new evaluation criterion. Even then, the instabilities described above persist.

A common response to these problems is to abandon numerical scores entirely and use boolean assertions: specific pass/fail checks for each test case. Research supports this approach for stability—binary judgments consistently separate clean from corrupted passages with low variance across runs.

However, there's a fundamental information loss. To capture the same granularity as a 10-point scale, you would need a separate boolean assertion for each point on that scale. In practice, teams end up with a sparse set of assertions that collapse meaningful quality distinctions into binary outcomes.

The problems with LLM-as-judge stem from a fundamental mismatch: language models output discrete tokens, not calibrated measurements. Asking a model to "rate this response from 1-10" forces it to map a complex quality judgment onto an arbitrary numeric scale it was never trained to use meaningfully.

Composo takes a different approach. Rather than asking models to generate scores directly, we use them for what they're good at—reasoning about quality in natural language—and handle scoring through a purpose-built reward model trained specifically on quality distributions.

This separates the judgment from the measurement.

Composo uses a Generative Reward Model architecture that combines post-trained frontier models (up to 8 models, ensembled) with a custom reward head.

The reward head is trained on 1M+ expert-labelled data points from three sources:

When a trace and evaluation criteria are submitted, the system assesses input complexity and ambiguity. Straightforward inputs with clear criteria are processed through a faster evaluation path. More complex or ambiguous inputs are routed to more extensive processing. This allows sub-second results on simple cases while maintaining full accuracy on harder ones.

Based on complexity routing, Composo generates multiple reasoning traces using an ensemble of up to 8 frontier-class models—including Claude, OpenAI, Qwen, and Gemini.

These models are post-trained specifically for critical analysis rather than helpfulness. Standard LLMs are RLHF'd to be helpful, which makes them optimistic, sycophantic, and prone to conflating quality dimensions. Our reasoners are trained for rigorous criteria adherence—they focus on the specific rubric and parse dimensions independently, rather than drifting toward "seems good overall."

Each model produces its own reasoning trace, creating a distribution of analytical perspectives.

Rather than asking models to generate numerical scores, Composo passes the reasoning traces to a custom-trained regression-based reward model.

This is a Llama backbone with the language modeling head replaced by a regression head (linear layer with sigmoid activation). It's trained using the Bradley-Terry framework on millions of pairwise preference comparisons—similar to Elo ratings in chess.

During training, expert labellers review outputs across domains and indicate which of two outputs is better. Through millions of these comparisons, the model learns the quality spectrum from relative judgments rather than arbitrary numeric anchors. Rather than being told "this is 7/10 because it has minor errors," the model learns through comparisons: "Output A is better than B because it's more accurate, but C is better than A because it's more complete."

The result: stable 0-1 scores to 2 decimal places. The same input produces the same score. A 0.3 is always meaningfully worse than a 0.7—not just on a different day or with a different prompt.

The system collects scores from all reasoning traces and takes the median. The output includes:

Standard evaluation has no memory—every assessment starts from scratch. A human expert builds intuition over time: they remember edge cases, learn what patterns correlate with problems, calibrate their sense of "good" against everything they've seen. Traditional automated evaluation doesn't learn.

Composo maintains a per-customer memory store containing your full evaluation history and ground truth data. Every evaluation retrieves from this store, and every evaluation enriches it.

When evaluating a new trace, the system performs adaptive retrieval:

Exact match anchoring: If the trace matches an entry exactly, the system anchors fully on that example's score. This guarantees determinism—identical inputs always produce identical outputs.

Similarity-based retrieval: For traces that are semantically similar but not exact matches, the system retrieves relevant examples to inform scoring. A new response about return policies will be scored in the context of how similar return policy responses were scored previously.

Spectrum coverage: The retrieval mechanism deliberately spans the full 0-1 scoring range. If retrieval would only surface high-scoring examples, the system includes lower-scoring calibration data. This prevents score distribution collapse—a common failure mode where all scores drift toward the mean.

Uncertainty filtering: Examples with high-confidence scores are weighted more heavily than uncertain ones.

Here's how this works in practice. When a new customer runs their first evaluations, the system scores them using the base reward model trained on our general corpus. These early scores are accurate but generic—they reflect what "good" means across all domains.

As the customer runs more evaluations, the system builds an internal representation of what scores mean in their specific context. By evaluation 500, memory has learned patterns: this customer's responses that score 0.8+ typically cite sources inline; their 0.4-0.6 range usually indicates correct information with formatting issues; below 0.4 means hallucination or off-topic responses. The system isn't told these patterns—it learns them from the distribution of actual outputs.

This means scores become increasingly calibrated to your quality bar, not a generic one. A legal tech company and a customer support bot might both care about "faithfulness," but what constitutes a 0.7 looks different in each context. Self-calibration handles this automatically.

Memory is dynamic by default—accuracy converges toward true values as your history grows. For reproducibility, you can pin memory to a timestamp.

Self-calibration works without any customer-provided data. However, for use cases requiring explicit domain grounding, additional data can be added to the memory store:

This data integrates into memory and influences retrieval in the same way as self-calibrated data. Exact matches in golden data fully anchor the score; similar examples inform proportionally.

Academic benchmarks often focus on artificial tasks that don't translate to business needs. We validated Composo using PrimeBench, a benchmark constructed from diverse domain-specific challenges in real-world industry tasks. More detail on this work is available here.

PrimeBench integrates data from multiple sources requiring different capabilities:

We compared Composo Align against state-of-the-art LLM-as-judge implementations (Claude Sonnet, GPT-4.1) and RAGAS. For each test case, we conducted pairwise comparisons measuring agreement with expert human evaluators.

Composo achieves 95% agreement with expert evaluators compared to approximately 70% for LLM-as-judge approaches (71.5% Claude Sonnet, 71.0% GPT-4.1, 53.5% G-Eval, 47.7% RAGAS). This represents a 6x reduction in error rate.

Accurate evaluation requires visibility into what actually happened. You can't score an agent's performance if you can't see the decisions it made, the tools it called, or the intermediate reasoning that led to its final output.

Many agent frameworks abstract away underlying LLM calls, making it difficult to understand behaviour and evaluate performance. An orchestrator calls a planner, which calls a researcher, which makes three LLM calls—and all you see is the final response. When something goes wrong, you can't tell which component failed.

Composo provides a tracing SDK that instruments LLM provider APIs (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google GenAI) and allows marking of agent boundaries. This gives you the visibility needed for meaningful evaluation.

A key difference from other tracing systems is that Composo tracing returns a trace object directly in your code via the context manager's with variable. This enables immediate local evaluation without exporting data to an external platform:

The tracer.trace object is available immediately after the context manager exits. You can evaluate it locally, make decisions based on the scores, or take corrective action - all within the same execution context. There is no requirement to push traces to a remote system and wait for async results. This makes it practical to use evaluation results to influence runtime behaviour, gate deployments, or trigger alerts without external dependencies.

The tracing system supports nested agents for hierarchical multi-agent architectures. Parent-child relationships are captured automatically when AgentTracer contexts are nested. The compiled trace includes all LLM calls made by each agent, and evaluate_trace() returns per-agent evaluation results with summary statistics (mean, min, max, standard deviation) for each agent independently.

Any natural language criterion can be used (single sentence, starting with 'Reward...' or 'Penalize...'). For common use cases, Composo provides pre-built criteria frameworks.